So the Houston Astros will be moving to the American League in 2013, giving each league 15 teams. How will this affect pricing in each league?

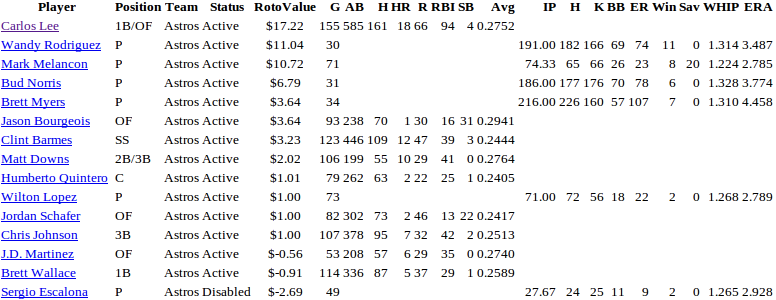

It turns out it won’t make much difference at all. The Astros were, by far, the weakest NL team in terms of RotoValue of their players. Assuming a $260 salary cap for 10 fantasy teams in a 5×5 league, the average NL team should have $162.50 in value. The Astros had barely a third of that, just $62.31 in cumulative RotoValue from the 12 players with a positive price (I ignore negative values for players in such totals, because in theory players with negative value shouldn’t be owned).

For a National League player pool, that’s just 2.4% of the value leaving the league. To see the impact on NL prices, I tried moving the Astros to the NL, then recomputing values for both AL an NL leagues, keeping their statistics the same, as if the Astros had been an AL team in 2012.

Since 12 Astros would no longer count as NL players, the next 12 best players that had negative value before would now be worth the $1 minimum bid. Removing the 12 Astros with positive value also affects the replacement level for each position: a slightly worse player is now the weakest player who should be in a starting lineup, so an extra $50.31 in value is spread among the remaining 268 owned players. So an average player would see his price rise by $0.19, much less than the assumed $1 minimum bid.

When I did the exercise, I was surprised to find out that some of the best players actually saw their prices drop a little: Matt Kemp fell the most, from $48.23 to $47.87, while Ryan Braun fell from $42.57 to $42.27. All the players whose prices fell were either outfielders or pitchers, and they only fell by fairly small amounts – Kemp’s $0.36 drop was the largest.

Players who previously wouldn’t have been owned, but now were worth $1, saw the largest rise in value. Corner infielders saw their prices rise by more than average – Albert Pujols went from $33.30 to $33.90, a $0.60 raise, and most other corner infielders saw somewhat larger price gains. Why this discrepancy?

The RotoValue pricing model determines positional value by “replacement”. Effectively the “replacement” level is the best player that shouldn’t be in someone’s active lineup for a given position. The model converts a raw value for each player into a net value, where the net value is the player’s raw value minus that of his replacement player. For players worse than replacement, this results in a negative net value (and, thus, a negative price), while players better than replacement have positive net value (and thus a positive price). The higher the net value, the higher the price.

So by removing 12 players from the pool of owned talent, not only is there more money to spend, but also the replacement level player at a given position is a little worse than he was before. And that difference in value varies by position. The smallest difference was for outfield, while the largest was for 1B (and 3B). So under the model, removing Astros players weakened the corner infield pool more than it weakened the outfield pool, so corner infielders captured more of the extra money, and indeed the very best outfielders (and pitchers). In a league with a $1 minimum bid, the differences are too small to be significant. Maybe they justify going an extra dollar on a player, but no more than that.

Now if the Astros were a better team, the impact of them leaving would be larger. Just for fun, I reran NL prices assuming the Phillies moved to the AL instead. The Phillies were one of the best fantasy teams with over $260 in positive RotoValue from 18 players. Doing that boosted prices more – Matt Kemp gained over $2, from $48.23 to $50.29; Clayton Kershaw rose from $37.44 to $38.97. The average player would see a price rise of almost $1.

The Astros are the team whose move would cause the least impact on fantasy baseball.